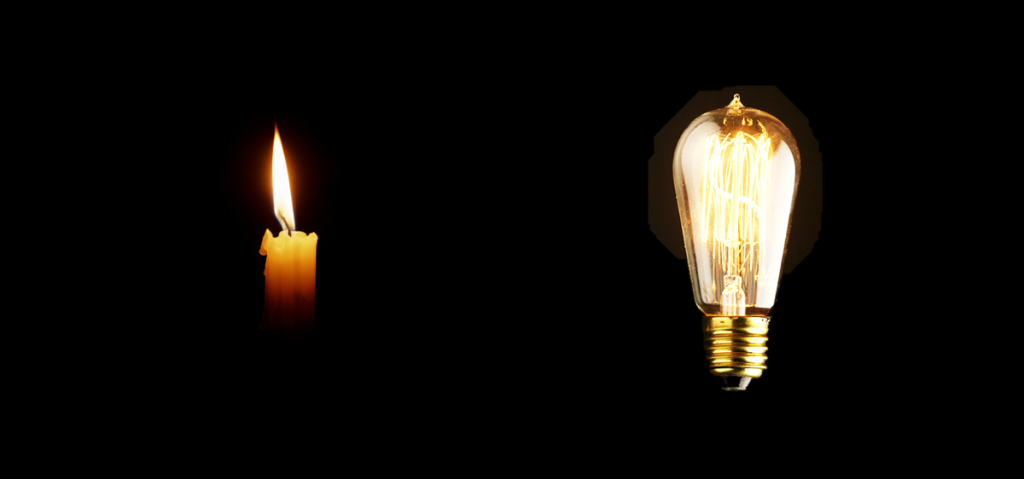

The invention of the incandescent bulb was bad news for candle makers.

Their product had been an indispensable part of both work and home for millennia (and had even survived the introduction of gaslight) but it was no match for Edison’s electric wonder… by the 1920’s demand had shrunk to birthdays, religious holidays and the occasional blackout.

It’s a classic example of what the economist Joseph Schumpeter called ‘creative destruction’: with every great idea comes the sudden birth of new industries and the slow, lingering death of old ones.

But Schumpeter didn’t factor in the hippies.

To the Flower Power consciousness of the 1960’s, the candle was a mystical symbol of The Age of Aquarius, a guiding light to a whole new generation: people who’d never thought of candles as lighting but as something magic, cosmic, tantric.

By the 70’s candles were romantic.

By the 80’s they were sexy.

By the 90’s they were scented and flavoured and therapeutic and pricey.

Today the candle market is worth £93m in the UK and $2.3b in the US and grows at around 10% per year; a cheap necessity of the 19th century has become an expensive luxury in the 21st, because an old industry asked itself new questions. Thanks to shifting social norms, a little innovation and a few hippies, candle makers have added a footnote to Schumpeter’s theory:

Just because you’ve gone from absolute to obsolete doesn’t mean you can’t come back again.

dave isles

did the candle industry come back to what it was or just find a small survival niche, Jason?

comparisons with vinyl records?

cheers, Dave I

Jason

Nice question Dave, there’s two different answers. There’s no way the demand for candles is anything like it used to be; it was THE predominant light technology for nearly 2000 years, it was the sort of thing you could not imagine functioning without (perhaps like the internet today?). On the other hand, I doubt the candles back in 1 AD retailed at $200 each, so in terms of dollars it could be the market is bigger now than it had ever been.

I like the comparison with old records but I think there’s a few big differences: I know a few vinyl enthusiasts and I think of them as a dying breed of passionate die-hards competing over a shrinking stockpile of products not manufactured since around the 1990s. Like tin robots and swap cards, vinyl records are (as you rightly say) niche collectables, not mainstream consumables and although I don’t have figures on what the market is worth, I’d be surprised if it was measured in the billions. By contrast, I’d argue the candle industry has created new uses (and users) for their product, which they are still busily developing and producing for a market that grows by 10% per year. And now there’s a few serious multinational chemical corporations like P&G in the candle racket… I can’t see Time Warner and Fox get into LPs and 45s can you?

Thanks for the comment Dave. Keep ’em coming!