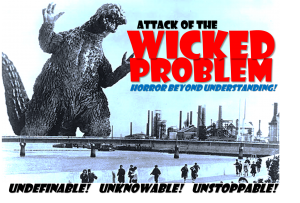

Imagine a problem so mysterious, so fluid and so fiendishly complicated that it was impossible to comprehend, let alone solve.

For a start, this nightmare problem would be essentially undefinable; you’d never actually know what the real problem was until long after the solution had been attempted… by which time you’d realise you’ve solved the wrong problem. The problem would be unprecedented, unlike anything human beings had ever faced. Nothing that had ever been learned from any other problem in history could be adapted or applied in any way.

There would be no best solution, only a least worst one, and you would never know if it worked or not. And if that wasn’t terrifying enough, in this horror show you would only get one shot to solve the problem before it shapeshifts into an even bigger monster. (Be afraid. Be very afraid.)

Forty years ago two design theorists (Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber) described this theoretical nightmare and gave it a scary name: The Wicked Problem.

The idea was an instant hit at the Pentagon, as it gave an convenient explanation for the mess in Vietnam. ‘Hey, we didn’t screw up’ they said, ‘war is wicked… unknowable, unpredictable and unending. You just gotta go with your gut and hope for the best’.

Economists weren’t far behind; ‘the economy is wicked’, they said, ‘we can never really know what to do, so why not let the market decide and see what happens?’ Wickedness has been a godsend for our politicians, who use it as a convenient label (and escape clause) for any issue that requires any kind of effort at all; today the phrase ‘wicked problem’ is short-hand for ‘no-one can fix this, so stop expecting me to.’

In recent years we’ve seen poverty, crime, homelessness, drug addiction, the road toll and unemployment declared as ‘wicked’ on their way to the Way Too Hard basket.

What’s next? Childhood obesity? Traffic jams? Junk mail? Tooth decay?

I’m sure some problems are truly wicked; our climate problems seem to fit the criteria very closely, and for all I know macroeconomics might run a close second. But the vast majority of the challenges facing us right now are not undefinable, unique or mysterious shapeshifting monsters; they’re relatively straightforward problems that have gotten big and ugly simply because we’ve ignored them for such a long time.

Whenever we imagine a problem to be a monster, we leave it for our grandkids to fix.

And that’s truly wicked.

There are No Responses to this post. Jump In!